Sunthetics is developing a more efficient and sustainable path to make a chemical intermediate for nylon. Nylon is used in a variety of industries, from textiles to plastics, yet is one of the most unsustainable manufacturing processes, releasing millions of tons carbon dioxide every year. One of the main reasons is that the majority of production inputs heat as a source of energy, which heavily relies on fossil fuels. At Sunthetics we’ve been able to develop a process that uses electricity as a source of energy, inputting renewables like solar directly into our reaction, and also reducing the need for petroleum-derived raw material by 50%. Simply put, our process uses less and more sustainable resources. If you want to learn more, feel free to check out our website and contact us!

Since we work with early supply chain chemical companies, our most essential customer feedback and validation comes from decision-making officers at large chemical companies. That means that our customer interview pool is ridiculously small and difficult to reach. It also means that these interviewees will most likely be our direct and only customers, so we have to tread carefully when navigating these relationships. We started the feedback process by asking questions to validate our market and product, all while not divulging too much information. We thought asking open-ended questions would be the best way to get valuable insight from these officers.

Unfortunately, human nature doesn’t work that way. It quickly became clear that speaking in hypotheticals or asking general questions generated limited value. For example, when asking about the decision-making process to integrate new products or new technology, the answers would vary. We heard “it goes through a couple departments” or “it takes about a year”, but never actual details. On top of that, whatever we were offering (whether licensing the technology to them or selling them the chemical directly) always sounded “fine.” Basically, there was no obvious objection but also no guarantee that these businesses would put their money where their mouth is.

So it became clear we needed to take a more experimental approach and generate higher value answers, much like the graph depicted in Testing with Humans.

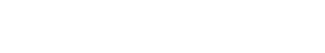

Circling back to the decision-making process example: we realized that in order to get more detailed answers, we needed to show these interviewees some kind of assumption, even if false. It turns out pointing out and correcting mistakes is much more effortless than summoning the actual answers. So we put together a basic flow-chart of what we thought was the hierarchy in these companies (see Figure 1) and showed it to our interviewees. We put this together in 10-15 minutes based on our previous interviews and logical assumptions. We let them make any organic comments and changes. Then, we asked them 1) if they could correct at least one thing what would it be and 2) which part of the process was the most annoying/time-consuming/problematic.

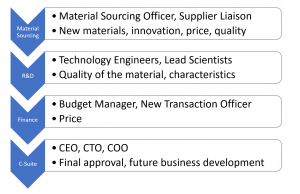

Not only did the interviewees correct us on some of our assumptions, such as the CEO not being an integral part of every major manufacturing decision, they also helped us discover the smaller intricacies involved as well as multiple points of entry for new technology (see Figure 2). Details about the motivations of the different departments within companies helped further refine our business model (this link explains everything in detail), especially regarding customer segments and value propositions.

Our main takeaway during this exercise was that there is information that simply can’t be revealed by just asking open-ended questions. The simple combination of a stated assumption with a visual representation helped us get answers we were previously unable to find. I also want to add that experiments don’t always necessarily have to do with your product. In our case, we are still too early stage and operating in a much too complex industry to be testing product-related assumptions. But we were still able to use experiments to test other parts of our business model, such as customer segments, value propositions, or even revenue model and pricing. So, whether you have a works-like, looks-like MVP, or are still trying to figure out who to sell to, it’s never too early to turn those conversations into experiments!