Picklock (formerly Skeleton Key), an NYU startup led by Mary Georgescu (Tisch MFA ‘20) & Connor Carson (Tisch MFA ‘20), share lessons learned through their participation in the Prototyping Fund.

When we began our prototyping journey in the Fall of 2019 we wanted to answer the question: How can we abstract the process of lockpicking? Originally we wanted a hook for our adventure game, Skeleton Key. We believed it would be thematic and exciting if we could have a controller that forced our players to engage with the world the way our character, a professional lockpick, engaged with the world. We thought the alternative controller would help immerse players. We didn’t even know if we could make an alternate controller, let alone that it would come to find a unique audience.

Fake it till you make it

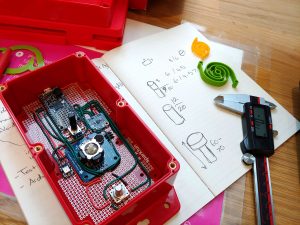

The first iteration of the controller used two joysticks and had two 3D modeled and printed, picks which read vertically and horizontally. Essentially, it read to our computers like an xbox controller. This was great for getting our feet wet and figuring out some basics of what products we were using such as: microcontrollers, buttons, and joysticks. We learned how to wire everything up on a breadboard. It gave us the initial step of trying to read a data sheet and figuring out the limits and capabilities of the microcontroller we were trying to use. It was during this initial step that we were able to attempt playtests with the maze-like puzzle that would get a player from room to room in the initial version of the game.

Look and Feel

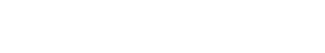

However, after toying with a real lock picking toolset we wanted to make it even more realistic and add a tension wrench. This dramatically complicated the programming since we could no longer lie to Unity and make the controller read like an xbox controller. It even showed us the folly of relying on other developer’s libraries which were dramatically outdated for the hardware we were using. Once we succeeded and managed to get beyond the breadboarding stage of the controller that included a potentiometer for the tension wrench we learned to solder. Having a physical case gave us the ability to playtest since we didn’t have to worry any longer that someone would accidentally unplug a component (which would happen every time because players would get excited and not notice.) That then helped us rapidly iterate on the puzzle design.

A Shift of Focus

Unfortunately, we had also inadvertently created a controller that spoke very well to the puzzle portion of the game and not necessarily the whole game overall which kept changing and expanding. Time was ticking and the designs were not meshing. After rushing to compile a whole universe and a whole narrative around an endless library within seconds of our final presentation for the fall we came to realize that we were just not going to be able to fulfill our vision. So we turned to our players. The consistent positive feedback that we were getting was the controller and the lockpicking puzzle felt good and felt engaging. After some very tough and heart wrenching design conversations we decided to split our larger team and two of us were going to hone in on the controller and lockpicking puzzle and make it feel as good as possible as a stand-alone arcade style game.

For the second semester and the second wave of funding, Picklock was born out of the ashes of Skeleton Key. New problems presented themselves as we took attention away from a narrative and honed in on the controller. Now our players wanted the controller to feel even closer to the act of lockpicking. While in the 1st prototype we were using similar tools as lock picks and mimicked using a pick and a tension wrench, the players weren’t sold on either tools because there was no tension and no reinforcement or feedback within the game to suggest that the task was difficult or that the tools might break or that something might go wrong. Everything was smooth. Too smooth.

We fabricated a spring in order to artificially create the tension as there was no manufactured potentiometer that had a spring loaded release to neutral like we needed. We changed out the components we were using and decided to add a form of haptic feedback through vibrations and lights, the same way xbox controllers were able to be programmed to react to the game. So far we were receiving data from the controller and using it within the game but we had not yet SENT data. This proved to be the trickiest and longest problem to solve because there were multiple steps involved and multiple problems from missing libraries to delays. We thought we were reaching the limitations of what the feather protoboard, our microcontroller, was designed to do.

Surprises during interviews

Throughout all of this prototyping we had no doubt in our mind that what we were working on was an arcade game. When we began talking to people and showing our project to complete strangers we learned that we were ignoring a whole market of potential players that were excited by the possibility of the game becoming a digital game you could encounter in an escape room. Across all levels of experience between digital game enthusiasts and analog game players for the most part they didn’t interact or cross but the exception was escape rooms, where both analog and digital players would engage in puzzle solving. This insight has helped us redirect the overall of the controller for the future and we may even someday soon see money from this prototype that started as a design inquiry.

Learn more by watching our game trailer!